The Supreme Court of Canada released its reasons in R v. Sharma on November 3, 2022. https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/19540/index.do

Here is the case history provided by the SCC:

In 2016, the respondent Ms. Sharma, an Indigenous woman, pled guilty to importing two kilograms of cocaine, contrary to s. 6(1) of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (“CDSA”). Ms. Sharma sought a conditional sentence of imprisonment, and challenged the constitutional validity of the two-year mandatory minimum sentence under s. 6(3)(a.1) of the CDSA and of ss. 742.1(b) and 742.1(c) of the Criminal Code, which make conditional sentences unavailable in certain situations. The sentencing judge found that the two-year mandatory minimum sentence under s. 6(3)(a.1) of the CDSA violated s. 12 of the Charter and could not be saved under s. 1. The judge therefore declined to address the constitutional challenge to s. 742.1(b), and he dismissed the s. 15 challenge to s. 742.1(c). Ms. Sharma was sentenced to 18 months’ imprisonment, less one month for pre-sentence custody and other factors.

Ms. Sharma appealed and, with the Crown’s consent, also brought a constitutional challenge to s. 742.1(e)(ii) of the Criminal Code. A majority of the Court of Appeal allowed the appeal. Sections 742.1(c) and 742.1(e)(ii) were found to infringe both ss. 7 and 15(1) of the Charter, and the infringement could not be justified under s. 1. The majority held that the appropriate sentence would have been a conditional sentence of 24 months less one day, but as the custodial sentence had already been completed, a sentence of time served was substituted. Miller J.A., dissenting, would have dismissed the appeal and upheld the sentence of imprisonment.

The outcome of the case is that the majority (Brown, Rowe, Wagner, Moldaver, and Coté) found there to be no violation of either s.7 or s.15(1) of the Charter. The dissenters (Karakatsanis, Kasirer, Martin and Jamal) came to the opposite position, finding violations of both.

The case is likely to generate lots of discussion, given the quite stark differences in how the majority and dissent (5-4 split) understood the challenges in front of them. Perhaps this will come as no surprise, given the number of interventions in the case (here is a link to the 23 facta filed in the case – Facta on Appeal). There is some powerful written and oral advoacy in this case, and there is much in here that could be profitably drawn into the law school classroom. Here is a quick link to the webcast of the case: Webcast of hearing in Sharma)

On November 7, there was a “Pop-Up Conversation on Sharma” at UVic law, with Professors David Milward, John Borrows, Patricia Cochran, Patricia Barkaskas and Rebecca Johnson, and Sentator Kim Pate and UVic law student Michael Davidson (2L in the JD/JID program). The point was to provide an introduction to the case, followed by a series of short (3-5 minute) interventions, attempting to start a conversation about the case, and about how to understand next steps forward in terms of addressing the crisis of over-incarceration. [On that front, here is a news item on the report of Correctional Investigator Ivan Zinger, released mere days before Sharma.]

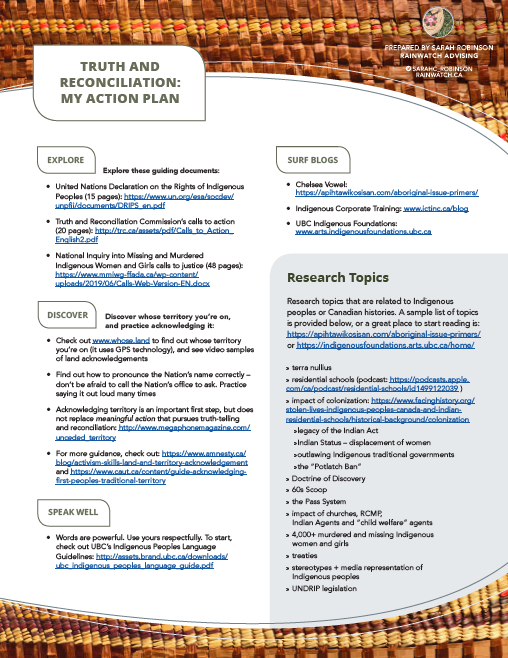

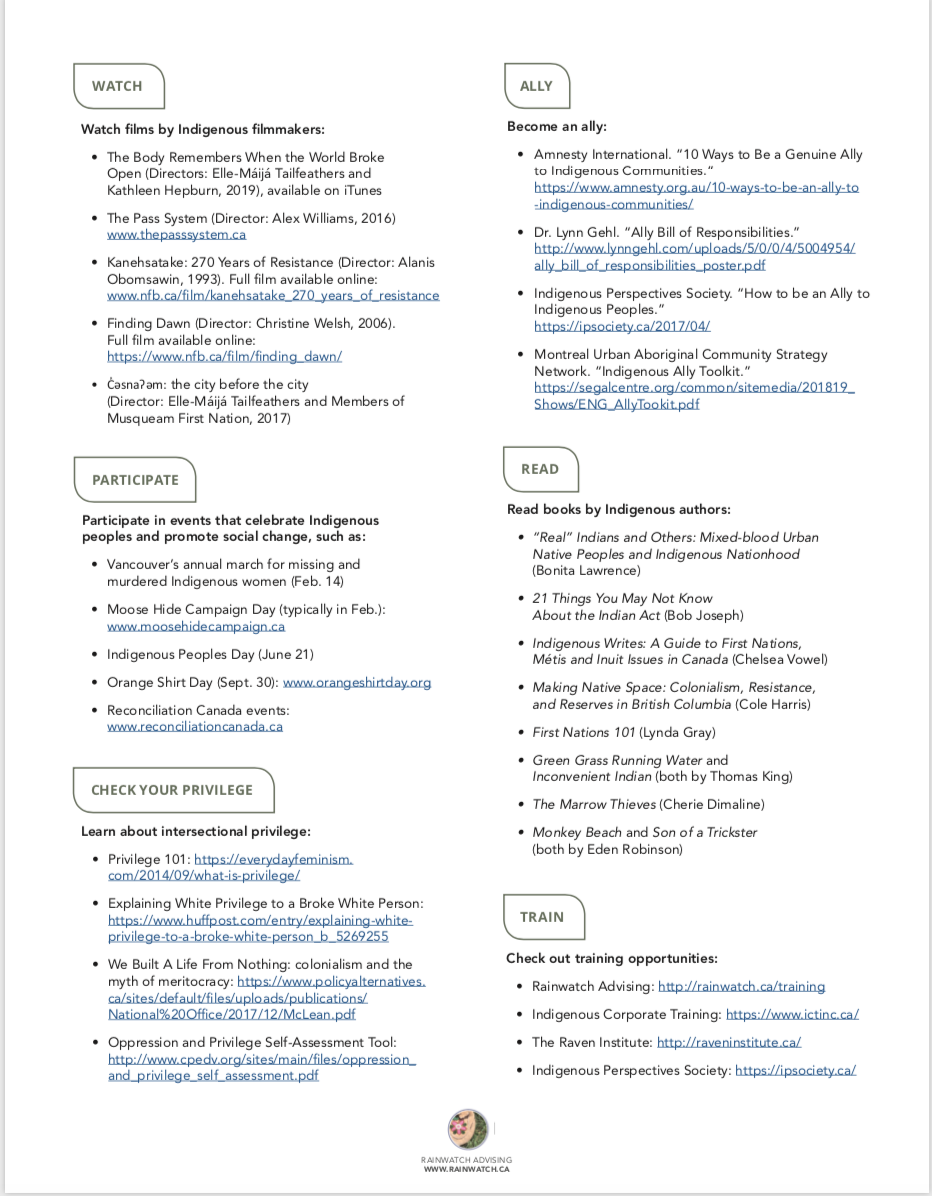

For the purposes of #ReconciliationSyllabus, we gather here some of the resources from that event, to share with folks who are trying to figure out how to be responsive to the TRC Calls to Action in engaging with both the majority and dissent in this case.

First, here is a link to an audio recording of the Pop-up-Panel.

| Rebecca Johnson (Introduction to the Case) | 00:00 |

| David Milward | 09:15 |

| John Borrows | 12:20 |

| Patricia Cochran | 18:00 |

| Kim Pate | 22:45 |

| Patricia Barkaskas | 28:15 |

| Michael Davidson | 36:30 |

| Questions & Conversation | 39:15 |

Second, here is a link to the handout prepared for the conversation.

Third, here is a link to the background powerpoint prepared by Rebecca Johnson for use in the Criminal Law classroom [it is open access, so feel free to use, modify, change, as you will…. and to disagree!]

The audience also took up the relationships between litigating and legislating for change, pointing to Bill C-5, which attempts to reduce the number of ‘excluded offences’ in order to create the discretion needed to build sentencing practices that respond to the TRC calls to incorporate Indigenous centred approaches to justice.

There is so much to be said about this case, particularly the majority and dissent engage in quite different ways with the challenges ahead of responding to and reversing the complete crisis of Indigenous over-incarceration in Canada, and particularly the over-incarcernation of Indigenous Women.

We know there are many resources out there to help us, in our law schools, engage with the challenges ahead. We would love for folks to attach to this post any additional resources (articles, links, teaching materials, ideas) in order to begin changing either the discourse, or the legislative framework or the shape of our conversations (both in our classrooms, and in the broader public).

I was reflecting on these recommendations this summer, while at the

I was reflecting on these recommendations this summer, while at the  Songhees Dance Group come and share with us a number of songs and dances. It was such a pleasure to watch the group, which included men and women, and dancers of all ages (adult, youth and children).

Songhees Dance Group come and share with us a number of songs and dances. It was such a pleasure to watch the group, which included men and women, and dancers of all ages (adult, youth and children).

Looking for a good read this summer, during COVID times? One of my favourite books of the year is Wendy Wickwire’s book, At the Bridge: James Teit and an Anthropology of Belonging (UBC Press, 2019).

Looking for a good read this summer, during COVID times? One of my favourite books of the year is Wendy Wickwire’s book, At the Bridge: James Teit and an Anthropology of Belonging (UBC Press, 2019).

My copy of the book pretty much looks like this….. I couldn’t help myself! (sorry to you librarian folk out there who try to maintain book purity). But the text simply drew me into engagement, and there were just so many things i wanted to be able to return to. While my kids (nearly adult man-cubs?) have not yet ‘read’ the book (physically run their eyes over the pages), they both have a good sense of what is there: while I was reading, I was constantly stopping to interrupt them in their other endeavours, so I could read them different sections from the book.

My copy of the book pretty much looks like this….. I couldn’t help myself! (sorry to you librarian folk out there who try to maintain book purity). But the text simply drew me into engagement, and there were just so many things i wanted to be able to return to. While my kids (nearly adult man-cubs?) have not yet ‘read’ the book (physically run their eyes over the pages), they both have a good sense of what is there: while I was reading, I was constantly stopping to interrupt them in their other endeavours, so I could read them different sections from the book.