“The Confederation Debates”:

Promoting Reconciliation in grade 7-12 Curriculum

Daniel Heidt, dheidt@uwaterloo.ca

Robert Hamilton, robert.hamilton1@ucalgary.ca

The pursuit of reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples is becoming more and more widespread, permeating unexpected aspects of Canadian life. Many teachers across the country are eagerly taking up this challenge, but sometimes struggle to find accurate and appropriate lesson plans to work with.

The Confederation Debates took up this challenge in one small area by developing mini-units for grade 7-12 teachers that bring Treaty histories into Confederation discussions. For historians and legal scholars, the term “Confederation” is usually constrained to visions of the 1864 conferences at Charlottetown and Quebec City with the likes of John A. Macdonald, George-Étienne Cartier and Leonard Tilley. A charitable few academics extend this to include the Red River Resistance (around present-day Winnipeg), British Columbia and Prince Edward Island, which all entered Confederation by 1873. Even these depictions leave out many of Canada’s provinces as well as Indigenous Peoples not present for the Red River Resistance.

The Confederation Debates challenges these preconceptions. In addition to expanding the temporal scope of “Confederation” to include Canada’s most recently added provinces and territories, its leadership wanted the project to affirm that Indigenous Peoples were — and continue to be — “partners in Confederation” (as the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples insisted). Thus, on the project’s website, treaty texts and records of treaty negotiation are positioned alongside the verbatim records of legislative debates about each province’s decision to join or reject Confederation.

While the project lacked the resources to reproduce the texts of all historic and modern Treaties, along with the records of their negotiation our team, a multi-disciplinary team comprised of Robert Hamilton, Daniel Heidt, Jennifer Thivierge, Bobby Cole and Elisa Sance, developed educational mini units that allow grade 7/8 and high school students across the country to develop a multifaceted understanding of their province’s entry into Confederation. To guide this team’s work, the project’s leadership sought the guidance of John Borrows, who provided helpful and regular oversight. Each mini-unit, catered to address each province’s curriculum requirements, is split into “parliamentary” and “Indigenous” sections. The former provides the research sources and original records necessary for an engaging mock parliamentary debate on a province’s entry into Confederation. The latter section contains two lesson plans about Indigenous peoples and their roles in shaping the country.

Confederation. To guide this team’s work, the project’s leadership sought the guidance of John Borrows, who provided helpful and regular oversight. Each mini-unit, catered to address each province’s curriculum requirements, is split into “parliamentary” and “Indigenous” sections. The former provides the research sources and original records necessary for an engaging mock parliamentary debate on a province’s entry into Confederation. The latter section contains two lesson plans about Indigenous peoples and their roles in shaping the country.

In developing these lesson plans, we sought to challenge historical narratives which minimize or erase the role of Indigenous peoples, providing an understanding of Confederation which recognizes Indigenous agency. This required rethinking notions of Confederation that construed Indigenous peoples as cultural minorities within a broader political community. These activities were developed to emphasize simplicity, Indigenous agency, and fiduciary obligations. To that end, the mini-units begins with a brief summary for teachers about conceptualizing confederation:

There are two very distinct stories we can tell about Confederation and Canada’s Indigenous Peoples. In one story, Indigenous Peoples are largely invisible. Here, their only presence is found in s.91(24) of the British North America Act, 1867, where “Indians, and lands reserved for the Indians” were deemed to be federal, as opposed to provincial, jurisdiction. This has subsequently been interpreted as providing the federal government with a power over Indigenous Peoples and their lands. The Indian Act of 1876, which is largely still with us today, was passed on this basis. This created what political philosopher James Tully has called an “administrative dictatorship” which governs many aspects of Indigenous life in Canada. Many of the most profoundly upsetting consequences of colonialism are traceable in large part to the imposition of colonial authority through s.91(24) and the Indian Act of 1876.

But there is another story as well. Canada did not become a country in single moment. Though the British North America Act, 1867, created much of the framework for the government of Canada, Canada’s full independence was not gained until nearly a century later. Similarly, the century preceding 1867 saw significant political developments that would shape the future country. Canada’s Constitution is both written and unwritten. Its written elements include over 60 Acts and amendments, several of which were written prior to 1867. The Royal Proclamation, 1763, for example, is a foundational constitutional document, the importance of which is reflected by its inclusion in s.25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Royal Proclamation, 1763 established a basis for the relationship between the British Crown and Indigenous Peoples in North America. By establishing a procedure for the purchase and sale of Indigenous lands, the proclamation recognized the land rights of Indigenous Peoples and their political autonomy.

Both the pre-Confederation and post-Confederation treaties form an important part of this history and what legal scholar Brian Slattery calls Canada’s “constitutional foundation.” It is through Treaties such as these that the government opened lands for resource development and westward expansion. It is also through the treaty relationship that Indigenous Peoples became partners in Confederation and helped construct Canada’s constitutional foundations.

Our challenge was to present narratives of Confederation that provide students with a glimpse into the complexity and pluralism in Canada’s founding in ways that were historically accurate and accessible for students in the grade ranges we targeted.

Towards this end, we developed two exercises focusing on Indigenous issues as part of the lesson plans. The first is a “leaving a trace” exercise that helps students to understand how cultural misunderstanding can come about, as well as how historical events are shaped by both the chronicler and the interpreter of historical narratives. The exercise requires students to silently draw their own recent activities or conversations and then ask their peers to interpret those ‘records’ without any contextual information. This exercise encourages students to think critically about the materials used in their second activity.

The second activity is a mock “museum curation” exercise where students learn about a Treaty in their province by breaking into groups to study one of up to six ‘artifacts.’ One group researches the treaty, other groups study Indigenous and Crown negotiators, and at least one group studies a cultural object that was important to the negotiations. For example, in the British Columbia exercise, groups receive one of the following:

- Text of a Vancouver Island Treaty

- Biography of Sir James Douglas

- Biography of David Latass

- Biography of Joseph Trutch

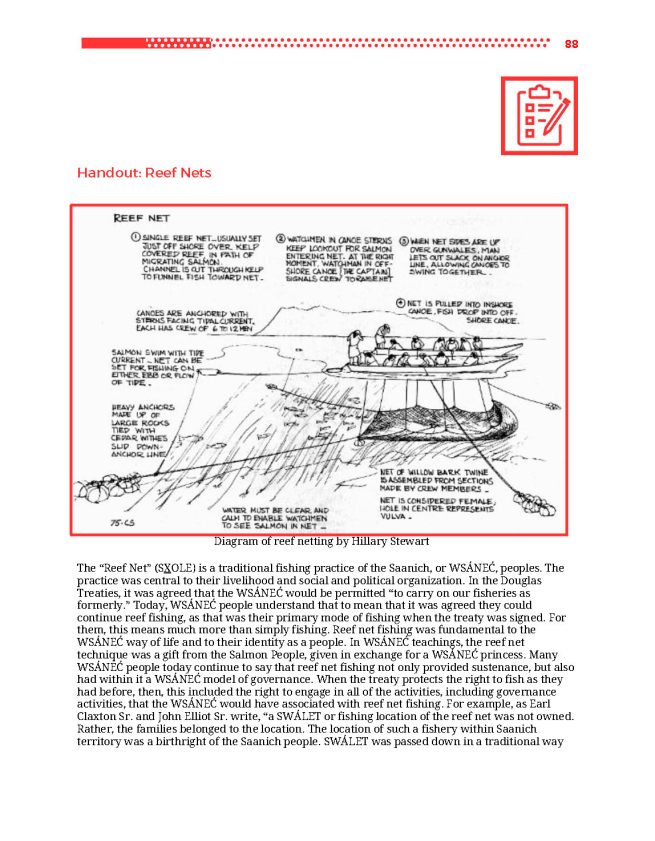

- Written description of the WSÁNEĆ reef net fishery

- Records of treaty negotiation and comments on treaty implementation

Each item or historical figure was carefully chosen for the historical information and perspectives they exemplified. Teachers also have a list of questions to guide discussion. The first group is provided with a text of one of the Vancouver Island Treaties. We felt that it was crucial for students to actually engage the text of treaty.

Using these ‘artifact’ records, each group is expected to produce an exhibit to share their findings (ex. a diorama, poster etc…) and the teacher then guides the class through the exhibit with questions designed by our team to spur discussion. In the case of the Vancouver Island Treaty, for example, the questions include:

- What rights and responsibilities are recognized in the treaty?

- The treaty uses complex and technical legal language. Did you find it easy to understand?

- Would it have been difficult for people who did not grow up speaking English to understand the language used?

- Which of the parties to the treaty might have benefitted most from having it written this way?

- How might current understandings of the treaty be shaped by the fact that the only copy is written in English and articulated in dense legal language?

- What might be missing from the treaty as it is presented here?

These questions were designed to help teachers to guide the students through a critical  reading of the text while developing their critical faculties. Some of the questions could elicit quite sophisticated answers. But we also believed that it could open students’ (and perhaps even teachers’) minds to new ways of understanding treaty relationships.In addition to these questions, The Confederation Debates encourages teachers to invite local Indigenous leaders to also join this tour, hoping that it will allow these local leaders to comment on the displays and raise important questions about representations of historical relationships and the nature of the Crown obligations undertaken in the treaties.

reading of the text while developing their critical faculties. Some of the questions could elicit quite sophisticated answers. But we also believed that it could open students’ (and perhaps even teachers’) minds to new ways of understanding treaty relationships.In addition to these questions, The Confederation Debates encourages teachers to invite local Indigenous leaders to also join this tour, hoping that it will allow these local leaders to comment on the displays and raise important questions about representations of historical relationships and the nature of the Crown obligations undertaken in the treaties.

Taken together, our team hopes that these activities will be one of the many tools that teachers will use to help their students explore history, historical narratives, Indigenous agency, and the meaning of Confederation. By helping students to learn that Confederation encompasses all of Canada’s provinces, territories and Indigenous Peoples, we hope to foster dialogues that will improve Indigenous and non-Indigenous relationships.

This work, however, is not yet finished. To complete its bold vision of educational materials, the project is still in need of volunteers. Despite undertaking considerable preliminary planning, the project ultimately lacked the resources to complete mini-units for the territories as well as Newfoundland and Labrador. If anyone is interested in co-developing the Treaty sections of these mini-units, please contact one of us and we’ll be happy to share the work completed to-date.